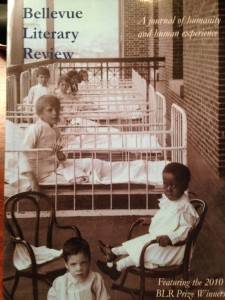

This story appeared in the Bellevue Literary Review, Spring 2010

This story appeared in the Bellevue Literary Review, Spring 2010

[available as a pdf here : Jeopardy]

At three in the morning Carla’s hospital room was utterly dark except for the white stripe glowing under the door. People on duty out there, a trained staff, wheeled things down the bright hall. The stripe concentrated the darkness of the room and made her isolation richer, more therapeutic, so much better than waking up in the middle of the night at home. At home, the streetlight leaked in around the curtain and her heart would start thudding and the ceiling would press down and she’d roll over, careful not to wake her husband, Willie. Then she’d squeeze her eyes shut and tell herself that she was worrying for no reason, that Howard was not parked outside the house, at the curb, watching. Surely he didn’t come every night.

She didn’t have to worry about that now. Three days ago, on her way home to Bethesda from her job at the US Forest Service headquarters downtown, she stepped into a crosswalk and a speeding D.C. police car hit her, popped her in the air and into the median, where she’d collided with a dogwood sapling before landing in a bed of daffodils, breaking both legs, an elbow and a rib and solving the problem of Howard, deus ex machina. The only thing she remembered about it was the crossing light; she was firm on the fact that she’d seen it, the blinking white silhouette of the little man, stuck forever mid-stride. She’d asked Willie not to tell her office where she was – who needed the visitors, the exhausting chitchat, the flowers and chocolate requiring thank you notes? “There’s something called HIPAA,” she said. She’d learned about it in orientation for her job as a communications specialist. “They can’t make you tell.” Howard would be going by her cubicle, slipping confused little notes in her top drawer. Maybe he was skulking around her house right now, unaware that inside was only Willie, oblivious.

“It’s all about living in the now,” one of the nurses (Ray?), a balding, tattooed man with a tiny ponytail had said that afternoon. He’d velcroed Carla’s legs inside soft pumps that continually inflated and deflated to prevent blood clots. And, other than the fact that she was thinking about this in the middle of the night, what the nurse had said was true. Mostly she thought of physical things, mechanics, logistics; she was organized by what was broken and what still worked, the presence of pain, the absence of pain. How to reach her chapstick, how to get someone to close the blinds. She thought out all the steps. It was satisfying to solve the ordinary problems of the day, her brain like an engineer emailing instructions from a remote location. A line that went into a vein in her arm had emptied a bladder full of fluid into her body one slow drip at a time. Now she urgently needed to pee.

And there was the pain, again, the carnivorous pain. It would begin and she would accept it and it would get worse and then worse, and still it was something to accommodate, her lot, the hard, specific, parasitic pain of her life, her responsibility. A syringe injected in her IV would make it go away, and even though she was used to pain now, the relief was always a little ecstatic breach because the pain had almost tricked her into forgetting how it was not to be in pain. She was going to find the button and call the nurse. She’d get the bedpan business over with and then ask for more morphine. That would make the pain go away. It would allow her to float back to sleep.

Three remote controls looped through the bed rails. One adjusted the bed many ways: higher and lower, head up head down foot up foot down. She had experimented with these buttons the first day, trying without success to attain the barcalounger level of comfort that they seemed to promise. Another button changed the channel on the television, though it did not turn it on or off. She had to ask someone visiting the room to do that– Willie or a nurse or one of the volunteers, one of the diffident teenagers clocking community service hours required by court order or the National Honor Society. Another button called the nurse. Now she pressed it twice.

After a few minutes the sturdy Eastern European who’d taken Carla’s blood pressure around midnight came in, switched on the light and pulled latex gloves from a box near the sink. She was perfect for the bedpan routine: foreign, kind, inarticulate. Female. So Carla went ahead with it, with the things that the procedure required. With the help of the nurse she was able to lift her butt onto the talcum-powdered edge. Then she let herself pee, willing herself past the ancient ban on wetting the bed, the taboo an automatic valve that she must now learn to control, letting the nurse help with the wiping up. Carla cooperated the best she could, lifting herself so the nurse could extract the sloshing pan of urine with minimum spillage.

“You velly strong voman,” the nurse said, after she dumped the pan out and flushed it away. Marta.

“Thank you. I really appreciate your help.” Common courtesy, Carla had found, could blot up some of the indignity. Marta was no doubt used to geriatric cases; there probably weren’t too many forty-two- year-olds on the bedpan. Anyway, it was over. Next, Carla asked, “Do you think I could have some pain medication?”

“I check,” Marta said.

Carla’s body was a continuum of pain, from one broken place to the next. She tracked the four-hour prescribed intervals between her doses, and now she waited, confident that Marta was coming back, soon, with the morphine. The waiting was lovely, the way it was lovely to sit at a table once you placed your order for a boiled lobster. Finally, Marta checked Carla’s wristband, read the label on the vial, and injected it into the IV. The morphine burned as it flowed through the veins in her hand, a sensation familiar by now, something she knew would pass quickly, the pittance it cost to cross the buffer between pain and sleep.

“You good now,” Marta said.

“Turn out the light, please,” Carla asked, turning her head away. “And shut the door behind you when you leave, please, Marta. Thank you. Thank you, Marta.” It was dark again, the velvet blackness exposed again by the tiny white stripe under the door. And here was the truth: these drowsy, solitary reprieves from pain were the purest form of joy Carla had ever known. And now came the sleep, and she was floating into a whale’s open mouth, sweet with krill, sheltered in some diving giant.

#

Howard had told her in the car that night six months ago, his fingers inching sweetly up her thigh, that the cells in the human body are replaced one at a time, “on an ongoing basis,” every seven years. It was a lie, probably, or an urban myth, but wouldn’t it be nice if it were true. She had thought about that, drunkenly, pulling her sweater over her head. This continuous slough of the tangible self. At a future point that would slip by unnoticed, she would shed the last of her body’s cells that had participated in sex with Howard, secreted, welled up and insisted and wallowed. The whole glandular experience of Howard – the frantic necessity to unbutton, unbuckle, to seize and consume him – reduced to the cellular level, all the components, the eyes, the fingertips, his cool thigh, naked against her as she hung on to the headrest, the car itself, all of it, planned for obsolescence.

#

This happened every single morning before dawn at the hospital: some young resident walked in, flipped on the fluorescent lights, and recited a script that smacked of training and consultants. “Mrs. Quarles? Good morning. I’m Dr.Child. How are you today?” The resident that morning, a woman perhaps a dozen years younger than Carla, articulated each of these words precisely, and a little too loudly, as if to cut through the mess of whatever pain, ignorance, or impending death she might encounter, cut through it with the steel of protocol. By now, her fourth and last day in the hospital, Carla was used to this.

“Fine.” With her right hand, the good hand, Carla dabbed away a smear of drool on her cheek. She’d been deeply, darkly, blissfully unconscious when the resident spoke to her.

“Wow, it’s cold in here.” The resident said this in a perfunctory way. The required small talk.

Carla had asked everyone who came in to turn down the temperature and now the air was perfect, chilly and pacifying.

The resident squinted at the thermostat next to the door, hugging Carla’s chart to her chest. “It’s fifty-seven degrees in here.” It was, Carla thought, this woman’s job to log her progress or decline. There was something smug in the clarity of her voice, something sanctimonious in the ponytail that was clasped in a broad barrette at the nape and hung straight on down her back.

“It’s great,” Carla said. “I love it.” She tried to stretch her legs but couldn’t. She could wriggle her toes, though. They worked fine. She had nice toes. She’d painted them in a pearly new shade, Luscious, the day before the accident.

“So you want me not to turn it up,” the resident enunciated.

Carla did not want the woman to touch the thermostat. The thought I hate you floated through her consciousness like a bit of raw sewage. With her right hand Carla grabbed the bed rail, hiking herself higher, answering the doctor’s questions. Did she have adequate support at home? Someone to help with the tasks of daily living? Of course.

Outside the wide window it was just starting to get light. The blacktopped parking lot glistened with rain. Visitors were beginning to arrive, scurrying under umbrellas. At the nurses’ station someone was arranging for the delivery of a wheelchair, a special bed, other things. Moving her broken body from this building to the car to the house would be a problem. Solving it was the day’s project.

“You’ll be more comfortable at home,” said the resident. Like all the doctors she inched toward the door as she talked. Doctors disliked bodies per se. They preferred papers, pictures, charts, tables and computer screens. They burst into rooms, hugging reports and almost immediately started backing away. Well, she must be fairly repulsive by now. Carla smelled bad; she hadn’t been able to brush her teeth properly for days; her hair was plastered to her scalp; hairs pricked out on her calves below the leg pump. A long scrape ran along her right cheek, a chain of tiny scabs, from where she’d collided with the dogwood in the median. The hospital had taken thousands of dollars of x-rays and MRIs and CT scans but no one had changed her nightgown.

Wait. How was this going to work at home? Carla wondered. But the doctor had gotten away. What about my morphine?

#

Willie arrived while Carla was eating lunch. He’d had a class that morning at Montgomery College, where he taught political science. “I got it all taken care of, all ordered, the hospital bed, the wheelchair, the walker, all this,” he said, looking at the form he’d been waving. “This durable medical equipment. DME. And the private ambulance to take you home. That’s the only thing Aetna’s not going to pay for.” He bent down and gave her forehead a ceremonial, ex officio kiss.

“How much does that cost?” Carla asked, because she knew that Willie wanted her to ask, so he could tell her, in his role as husband, that it didn’t matter. A lie. She studied her tray: chicken salad, cranberry juice, and a cup of butterscotch pudding sealed with a foil lid.

“Couple hundred bucks.” He’d rolled the form into a scroll and now he tapped it lightly against his open palm. “This is why we have a VISA card. Not to worry. God, it’s freezing in here.” He sat on the chair beside the bed. A few raindrops stood out in his dark, curly hair. He took off his glasses and leaned forward to clean them with the edge of the sheet, a gesture that struck Carla as both intimate and alien. Willie had a bald spot on the top of his head that, years earlier, Carla had enjoyed rubbing, pretending to invoke magic spells. Did he notice when she’d stopped doing that? That was long before Howard.

“This guy from your office called. Howard.” Willie finished polishing his glasses and put them back on. He seemed to know nothing.

“What did he say?”

“It was just a message on the machine. You want me to call him?”

“No. He’s just this strange guy from my office. Ignore it.” She was able to say this with utter honesty. God. And did Howard go to the house last night, watch the lights go off? One night last month she’d gotten out of bed at home for no reason and looked out the window, and she saw him there, under the streetlight, behind the steering wheel of his red Prius. He’d seen her see him. The next day she took the note she found in her desk to the shredder, concealed between the pages of a press release on the emerald ash borer. You found me.

He’s just a strange guy from the office. It was so true. Thinking it was like drawing a tight little box around him.

“Gertrude’s coming today.” She had to change the subject. “We have to give her some money.”

Willie put his glasses back on. “How much?”

“Sixty dollars. Cash.” This was calming, this talk. She knew what to say and what to expect.

“Fine.” This was what Willie said, in a voice both determined and put-upon, whenever he had to pay for something, anything. The maid had been her idea, to clean their house also her idea, two of many ideas of hers that he resented. That he was frugal was high on the list of the things that Carla knew she ought to appreciate. He frowned over restaurant tabs, skimped on tips, loved anything free or discounted. She’d taken to hoarding money, sneaking tens and twenties into a beaded evening bag in the upstairs hall closet. A couple of times a year she’d go to the bank and exchange the money for larger bills. Close to three thousand dollars were secreted away in that purse. Now she wouldn’t be able to get at that shameful stash for a long, long time.

They’d worn down little grooves in their marriage and settled into them, like the swales in their bed. Once, in a burst of effort, they’d tried counseling. They were given assignments in a stapled workbook designed to “build a mutually empathetic feedback loop.” Apathy is the gum disease of marriage, the book said. Like gingivitis, there were stages of decay. Communication is like flossing. Maybe they’d have stuck with it if the metaphors had been less dental. Less of a task of daily living.

#

Howard had come later, an isolated experiment in illicit carnal abandon. Getting drunk and making out and fucking, like high school. You wouldn’t really select Howard for this experiment, if you thought it out. He was the ageless, friendly guy in the office, detailed to the forest pests and pathogens team – the bug man. But he’d been there, an opportunity, and they were hidden where no one could see, and so she took it. He’d been so attentive at the goodbye party for the intern, gotten her talking about her work in the public affairs office, told stories about his fieldwork in the Berkshires, offered to drive her home after all the margaritas. Going up the Rock Creek parkway they shared a joint and ended up parked behind a large church in some neighborhood. He handed her the joint, carefully, their fingers fumbling together briefly, and then watched her inhale.

“We could go back to my place,” he said, with a short laugh, so the remark could play either way, as a joke or an offer.

“Why the hell not,” she said, letting out the smoke. Marijuana! What a throwback this guy was. Fabulous.

He took the last of the joint from her hand, pinched it out, and dropped it in the Altoids container he’d taken it from. That was when he put his hand lightly on her knee. “Tempting. Very tempting.”

He kissed her ear. “I don’t even own a bed,” he said softly. “Did you know that?”

“Where do you sleep?” There was the smell of smoke and citrus, the bristles of his face on hers.

“On the floor. Naked in my sleeping bag.”

“Wow.” He was licking her ear now, his hand on her leg.

He helped her with his button fly, when she struggled with it. A moment of awareness fluttered by – this? with him? – but it wasn’t nearly as important as everything else that was happening, the need to find the lever for the seat, to get past everything that was in the way. It was safe, wasn’t it, a safe, secret place for this, behind the dark, looming church, next to the dumpster. Afterward she asked him to take her to a subway stop. She needed to level out before she went home. The electronic sign over the tracks at the Cleveland Park station said a train was expected in twelve minutes. She sat on a cool concrete bench and dug in her bag for a comb and lipstick. What she would give now for a stick of gum. A glass of cold water, a toothbrush, a long hot sudsy shower. These she would get at home, if only she could avoid Willie long enough to straighten out. She must hide this carefully, her dangerous secret, like the cache in her beaded handbag. Could you smell it on her, the pot, the sex? People walked right by her, kept going, purposeful and occupied, listening to their music, talking on cell phones. Not one of them looked as if their underwear was damp, or in any way askew.

#

The private ambulance was scheduled for five o’clock. The pumps on her legs were gently cycling through, squeezing and releasing, and she figured she had an hour before she’d need the bedpan. Willie couldn’t just sit there with her. He couldn’t bring a book, or share a newspaper with her. So Carla persuaded him to watch Jeopardy. She got him to turn on the television and then she expertly cycled through the channels with her remote control. “See, there’s a whole Jeopardy marathon.” She couldn’t believe it was still on the air. As small child she’d watched it whenever her grandmother babysat. She’d snuggle up next to her, poking at the ashtray with the beanbag bottom that her grandmother placed on the sofa between them, amazed by all the exotic facts her grandmother knew. Why didn’t Willie want to do this with her? Yesterday, as an attendant rolled her down the hall for another MRI, there was a couple sitting near the elevator doing a crossword puzzle, the woman in a wheelchair with an oxygen tank and an IV, the man holding the folded-over newspaper and a pencil, leaning in. You didn’t need any great passion, you just had to want to pay attention to the same things at the same time, to enjoy figuring out the answers together. That would carry you. But Willie wasn’t really interested in Dustin Hoffman for $400 or Cats for $800. He obviously thought it was pointless.

“Wait, that’s, that’s typhoid,” Carla said. But she was wrong. Bubonic plague. Of course.

Willie said nothing, sat silently with a look of tolerance and boredom. He didn’t care about the dopey contestants, didn’t have a favorite, as she did, the guy with the quivering mustache. Carla was glad for the morphine. It kept her from dwelling on the sad fact that she and Willie lacked whatever it was that might make it pleasant to watch Jeopardy together in her hospital room. It was far too petty to complain about but it seemed to be the nub of everything that was wrong between them.

Willie left when Marta arrived to take her temperature and blood pressure. “Put sixty dollars on the counter, by the phone,” Carla said, as he gathered his raincoat. She hated to think of him doling out the bills — one reluctant twenty on top of another in Gertrude’s open palm. “Just leave it out for her.”

“Sixty dollars.”

“Yes. On the counter by the phone.”

“Fine.”

“Good.”

It was much nicer watching Jeopardy after Willie left. She kept on the show for hours before drifting off after her next dose of morphine. She closed her eyes during a question about First Ladies and woke up to a commercial where a smiling woman knelt beside a dog, fastening on a flea collar. It was the perfect channel for her, for someone at the hospital, slipping in and out of consciousness. People must have died like this, drifting away for good before they got to hear the right question to some answer posed by Alex Trebek.

#

One evening, about a month after Howard and the margarita party, Carla sat on their front steps at dusk drinking a mug of tea while Willie watched basketball in the living room. The huge oak trees that lined their short block leafed out in the spring in a nearly continuous, heavy, romantic canopy. It was one of the reasons she’d wanted the house, even though it cost more than they should have spent. They couldn’t afford any of the work needed on it either, but she wanted to replace the crape myrtle, to rebuild and widen the slate path, and make so many other improvements. The bats were out, their stealthy, determined flights briefly visible in the streetlight. They probably believed themselves to be camouflaged – wasn’t that the point of being nocturnal? – and that was why she found it so entertaining to watch them. A bicyclist turned down the street, coasting, gears audibly spinning. It was Howard, recognizable behind the helmet and the reflecting safety vest. She jumped up and walked quickly to the curb as he looped a leisurely figure eight under the streetlight.

“So this is where you live?” He stopped and stood, straddling the bike, looking at the house.

“Jesus Christ! Why are you here?”

He lifted the tiny rear-view mirror attached to his helmet. A droplet of sweat ran out of a long sideburn. “What a pleasant evening. What a pleasant home.” He picked up the water bottle from its holder on the bike frame and gestured with it toward the house, the yard, all of it. Carla looked back and saw the bright living room window, flickering with the light of the television. Inside Willie was undoubtedly in his usual spot on the sofa, holding the remote. A lush border of blooming azaleas cushioned the house against the lawn. Her mug was on the front stoop; two dormers projected from the roof like eyebrows. Howard took a sip of water, holding the bottle over his mouth and squeezing it. Then he pointed the bottle toward the house and squeezed it again. A glittering arc of water leapt out and instantly collapsed into the lawn.

There would be no basis for a restraining order, really, and no way to get it without involving Willie. Poor Willie, she felt horrible about Willie. Getting rid of Howard would be so much easier if she wasn’t married to Willie. Back through the screen door she could hear him clap three times at the game. She stepped closer to Howard and whispered, “You have to leave me alone. You can’t just show up.”

He put the water bottle back in its holder. “It’s a public street and a beautiful night. I’m not going to detour around the fact that you live a lie.”

Howard was the hero of some story he’d made up about them. He was destined to rescue her. In his story she’d no doubt end up slavishly devoted to him once she recognized him for the prince he was.

“How do you even know where I live?”

“It’s all up here,” he rapped his helmet with his knuckles. “In the vault.” He laughed, stood on his pedals and pushed off, then coasted down the block.

#

Around four o’clock the male nurse came in to inject an anti-coagulant into a roll of flesh that he pinched in Carla’s belly. She checked his nametag as he did it – it was Ray. “So, Ray, isn’t it time for some more pain medication?” she said. She affected a jaunty tone, to show what a good sport she was about all this. And, it sounded better, she’d decided early on, if you had to ask for morphine regularly, to ask for “pain medication” and not “morphine.” Her rib especially hurt right then and she wanted to get some more before she went home with just a prescription for pills.

“Don’t know about that, kiddo. If I’m not mistaken you’re getting a prescription for Percocet.” The IV had already been removed, but the plastic stump still protruded optimistically from her arm.

“Really?” If she played dumb, maybe he’d reconsider. They got things wrong all the time.

How was this going to work at home?

Ray discarded the needle in the sharps container near the sink. “Are you in pain?”

God yes. Didn’t they know that? “Yes.”

“What hurts?”

“Hips, pelvis, elbow, rib. Breathing. Especially breathing.”

“Right.” He was standing next to her, hands on hips, as if about to lead her in calisthenics. “Now, what’s your current level of pain, right this instant? Scale of one to ten.”

She’d never understood that scale. It assumed you knew how bad the pain could possibly get. “Eight?”

“Right,” Ray nodded with earnest sympathy, backing away. “Let me see what I can do.”

An hour later, two men, one burly and one skinny and both reeking of cigarettes, came and strapped her to a gurney, covered her with a blanket, and rolled her out the door. In the parking lot they pulled the blanket over her face to protect her from the rain. Underneath, Carla closed her eyes. The men were laughing, then the one by her head said, “little bump,” as they went over a curb. The blanket, a much-laundered blue cotton, smelled of a friendly combination of laundry detergent and diesel fumes. Ray had gotten her a Percocet and one more dose of morphine for the trip home. It was disorienting and fabulous to clatter along out in the mist, feeling the wheels roll beneath her, snug beneath the blanket, pain gone, pain evaporated, pain handed back to the god of pain to hang on to for a while.

When they arrived at the house, the men slid her from the ambulance. She could see Willie standing at the bottom of the walk, the hood of his raincoat up over his head. Just before they pulled the blanket back over her face again she saw the red Prius parked at the curb.

“Little bump here,” one of the men said.

“That guy’s here,” Willie said. “The one from your office. Howard. He helped me move the furniture to make room for your hospital bed.”

There were just a few more seconds. Perfect seconds: anesthetized and hidden from everyone. Carla inhaled the smell of detergent and fumes, felt the soft weight of the blanket against her eyelids. It had been so sweet.

–END–